San Diego may well be the prototypical Southern California city. Visually, it brings to life the timeless images evoked by the Beach Boys' 1965 pop classic, “California Girls”: sunshine, sand and palm trees. The weather is close to ideal—sunny and mild to warm practically year-round. Furthermore, the greater San Diego area is blessed with an abundance of scenic environments in which to enjoy all this climatic good fortune—from cliffs that overlook long beaches to wilderness areas such as the Anza-Borrego Desert, where spring brings an explosion of wildflowers (weather permitting).

Clean and casual, San Diego has a contemporary West Coast sophistication that belies humble beginnings. Reminders of the past, however, are strongly evident. Spanish influence is exemplified by the Spanish Colonial Revival architecture found throughout Balboa Park, the city's cultural centerpiece. An international flavor prevails as well, due to a strategic location facing the Pacific Rim and close proximity to the border town of Tijuana.

Clean and casual, San Diego has a contemporary West Coast sophistication that belies humble beginnings. Reminders of the past, however, are strongly evident. Spanish influence is exemplified by the Spanish Colonial Revival architecture found throughout Balboa Park, the city's cultural centerpiece. An international flavor prevails as well, due to a strategic location facing the Pacific Rim and close proximity to the border town of Tijuana.

Long before the first Europeans arrived, the California coast was inhabited by peoples who had probably migrated from the Asian continent by way of the Bering Strait. They subsisted on fish, acorns and wild game, developing their own hunting, gathering and farming techniques. The native tribes of Southern California were remarkably diverse in language and customs, and their peak population may have reached 100,000.

Portugal was the first European nation to actively pursue overseas exploration and colonization. On June 27, 1542, Portuguese explorer Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo set sail under the auspices of the Spanish Crown from Barra de Navidad, Mexico, a tiny port on Mexico's Pacific coast near Manzanillo.

Exactly 3 months later, Cabrillo and his men brought their open-decked vessels, the San Salvador and the Victoria, into the harbor of San Diego. He named it San Miguel in honor of the Feast Day of San Miguel, celebrated on Sept. 28.

Exactly 3 months later, Cabrillo and his men brought their open-decked vessels, the San Salvador and the Victoria, into the harbor of San Diego. He named it San Miguel in honor of the Feast Day of San Miguel, celebrated on Sept. 28.

The city's present name came from San Diego de Alcalá de Henares, a Spanish monk after whom the flagship of Spaniard Sebastian Vizcaíno, a later explorer who charted the coastline in 1602, was christened. Vizcaíno erased many of the place names Cabrillo had established. Despite the new appellations, the Spanish Crown all but ignored the region until it was ordered colonized in 1768.

The following year, Gaspar de Portolá arrived to establish a presidio, or military fortress, in Mission Valley near present-day Old Town. In his company was Father Junípero Serra, a Franciscan priest who founded the Mission San Diego de Alcalá, California's first mission (it was moved 5 years later to a more advantageous location several miles away). The mission was intended to establish a Spanish presence in the region. From there Serra ventured as far north as Santa Barbara and founded the first nine of a string of missions that served as the cultural and economic lifeblood of the territory.

By providing a safe refuge for travelers, the missions encouraged further exploration of the land and became links in a trade route between Mexico and San Francisco. They also—in the form of religious virtue—managed to bring a measure of civility to the prevailing isolation and harsh conditions. In all, 21 missions were founded and run by the Franciscans, and some 30,000 of California's native population tended their extensive agricultural and livestock holdings.

In 1821 a newly independent Mexico gained control of what it called Alta (Upper) California, and 4 years later San Diego was named the territorial capital. While Mexicans established homesteads in Old Town, the westward migration of American pioneers was in full swing. A doctrine known as Manifest Destiny took hold of the nation, espousing the belief that the United States was destined to occupy the entire North American continent.

Conflict inevitably ensued. The Mexican government broke off diplomatic relations following the U.S. annexation of Texas in 1845. When U.S. and Mexican troops clashed over the disputed Texas territory in 1846, war was declared. Less than 2 years later, under the terms of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, all of Mexico's territory above the Rio Grande and an irregular line extending to the Pacific came under official American control. When San Diego was incorporated in 1850, Old Town was its center.

During this period there were few indications that the young city was to become the metropolis it is today. The gold rush spurred growth in both Los Angeles and San Francisco, while San Diego seemed to lead a more insular existence. It took a shrewd developer, Alonzo Horton, and his purchase in 1867 of some 1,000 acres of land abutting San Diego Harbor to give a boost to the area's population.

The San Francisco merchant bought land (at 27 cents an acre) and practically gave it away to anyone who promised to build on it. His largesse made sound economic sense, for it brought the city's commercial center closer to its valuable harbor. Horton's foresight was largely responsible for the birth of “New Town,” or modern San Diego.

In 1870 a minor gold rush in the hills of eastern San Diego County further sparked development. Victorian-style commercial buildings sprouted up along 4th and 5th avenues between Broadway and Market streets, a few blocks inland from the waterfront; many of them have been preserved in the city's 16.5-block historic district known as the Gaslamp Quarter. The relocation of the downtown core continued when a disastrous fire struck Old Town in 1872, destroying some of the district's buildings (those constructed of sturdy adobe survived).

With the arrival of the Santa Fe Railroad, the area's first tourists began trickling in. Some stayed at the exclusive Hotel del Coronado, the creation of a pair of savvy financiers. The ornate Victorian accommodation, known as “the Del,” opened in 1888. More than 300 buildings lined the waterfront by 1900, and the harbor became a vital shipping point for the region's agricultural products. San Diego's population—which swelled with the railroad's coming but declined shortly thereafter—had climbed to nearly 18,000 by the turn of the 20th century.

The city also blossomed educationally. San Diego State University was founded in 1897, and in 1903 the Marine Biological Association of San Diego (which was to become the renowned Scripps Institution of Oceanography) established a modest laboratory in the boathouse of the Hotel del Coronado. San Diego's cultural milestone was the 1915 unveiling of the Panama-California Exposition.

The California Pacific International Exposition followed in 1935-36, and the lasting legacy of both world fairs was the development of Balboa Park, a 1,200-acre urban refuge that was set aside in 1868 but essentially had remained a wild preserve of canyons and rocky hilltops into the early 20th century. Today it is an oasis of serene parkland, landscaped gardens and pathways. Many of the original Spanish Colonial Revival and Moorish-style buildings constructed for the two expositions now house San Diego's largest concentration of museums. The world-famous San Diego Zoo also is in Balboa Park.

The event that kicked development into high gear occurred more than 2,500 miles away—at Pearl Harbor. Following the attack on Dec. 7, 1941, San Diego Harbor became home to the U.S. Navy's Pacific Fleet. The impact of the war was tremendous, bringing an increase in industry and a huge influx of military personnel, many of whom stayed on after the war ended. Today San Diego is the home of the largest naval air station on the West Coast and is headquarters for many Pacific Fleet operations.

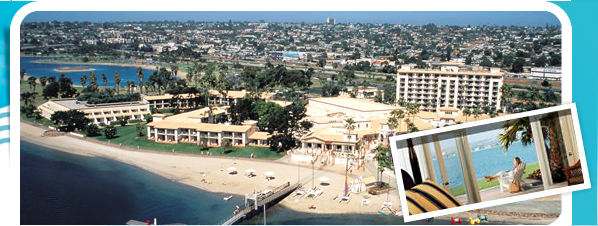

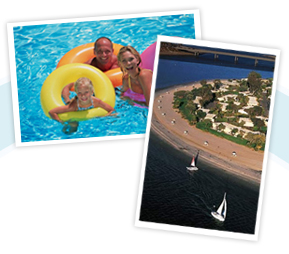

The forward vision of Alonzo Horton and Balboa Park's developers was repeated in 1960 when a massive land reclamation project began, resulting in today's 4,600-acre aquatic haven known as Mission Bay Park. Much of the swampy area was dredged in the early 1960s and replaced with wide lawns, man-made islands and sandy beaches. The combination of outdoor recreation, hopping nightlife and a casual, sun-and-sand atmosphere have made the Mission Bay area the residence of choice for many San Diegans. SeaWorld San Diego opened here in 1964.

San Diego's recent past has seen several significant events, such as the 1985 unveiling of Horton Plaza—an 11.5-acre complex of major department stores, specialty shops, restaurants and two performing arts theaters. Four years later the new convention center opened; its dramatic sail-shaped roof gave downtown a distinctive architectural landmark. In 2001, the convention center expanded, doubling its size. In addition, sleek skyscrapers sprouted, helping to elevate San Diego's formerly low profile.

A feather in the city's promotional cap was its hosting of the 1996 Republican National Convention, part of the “Star-Spangled Summer of '96” celebrations that included the San Diego Zoo's 80th birthday celebration.

Today San Diego is the nation's eighth largest city, with about 1.2 million residents. Business and pleasure coexist in harmony here; the city's climate, attractive scenery and recreational facilities promote a casual lifestyle that has enticed many visitors to become permanent residents. Not bad for a town that began with one small adobe chapel on a hilltop.